Table of contents

Open Table of contents

The Problem

Every growing team eventually faces the same infrastructure headache: who has access to which server, and what did they do there?

The usual answers — sharing SSH keys over Slack, maintaining an ever-growing authorized_keys file, or deploying a full-blown PAM stack — all fall apart at different scales. Commercial bastion hosts solve this, but they come with licensing costs, SaaS lock-in, or operational complexity that a 5–50 person team simply doesn’t need.

Jump is my answer to that gap. It is a single Go binary that acts as an SSH jump server with centralized authentication, fine-grained permissions, optional TOTP two-factor auth, full command audit logging, and a web-based admin UI — all backed by a single SQLite file.

High-Level Architecture

┌──────────┐ ┌─────────────────────────────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ Client │──SSH──▶│ Jump Server │──SSH──▶│Remote Server │

│(Engineer)│ :2222 │ ┌───────────┐ ┌────────────────┐ │ :22 │ (Production) │

│ │◀───────│ │ SSH Front │ │ Admin HTTP UI │ │◀───────│ │

└──────────┘ │ │ Door │ │ :8080 │ │ └──────────────┘

│ └─────┬─────┘ └───────┬────────┘ │

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ ┌──────────────────────┐ │

│ │ SQLite (jump.db) │ │

│ └──────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

The binary exposes two network listeners:

- Port 2222 — the SSH front door that engineers connect to.

- Port 8080 — a Bootstrap-based admin UI for managing users, servers, credentials, and permissions.

Both share the same SQLite database through GORM, serialized by SQLite’s built-in write lock — no external database required.

Why Go and Why These Dependencies

| Dependency | Purpose |

|---|---|

golang.org/x/crypto/ssh | Native SSH server and client implementation |

gorm.io/gorm + gorm.io/driver/sqlite | ORM with auto-migration for the schema |

go.uber.org/zap | Structured JSON logging |

Go’s x/crypto/ssh package is the keystone. It lets us implement a full SSH server and a client in pure Go, without shelling out to OpenSSH. This means the proxy path — accepting an inbound SSH channel and forwarding it to a remote server — is handled entirely in-process with bidirectional io.Copy goroutines. No temporary sockets, no file descriptors leaking between processes.

SQLite was a deliberate choice over PostgreSQL or MySQL. A bastion host typically manages hundreds of users and a few dozen servers, not millions of rows. SQLite gives us ACID transactions, zero operational overhead, and a single-file backup story. If the team outgrows it, swapping GORM’s driver is a one-line change.

The Data Model

The permission system is the heart of Jump. It uses a normalized, link-based model to decouple servers from credentials from users:

User ──┐

│ permission

▼

┌───────────┐ ┌────────────────────────────┐

│ Permission│──────▶ │ remote_server_and_auth_link│

│ (expiry) │ │ (server_id + auth_id) │

└───────────┘ └────────┬──────────┬────────┘

│ │

▼ ▼

┌─────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐

│remote_server│ │remote_server_auth│

│(ip, port) │ │(key or password) │

└─────────────┘ └──────────────────┘

Six tables total:

- user — name, email, SSH public key, optional OTP secret.

- remote_server — hostname/IP and port of a target machine.

- remote_server_auth — a credential (SSH private key or password) plus a login username. This is intentionally separate from the server because multiple servers may share the same deploy key, and one server may be reachable with different accounts.

- remote_server_and_auth_link — the M:N join between servers and auth methods. “Server A can be reached using Credential X.”

- permission — grants a user access to a specific link, with an optional expiration timestamp.

- operation_log — append-only audit trail: login, connect, every command typed, and disconnect.

This separation pays off quickly. When you rotate a deploy key, you update one remote_server_auth row and every server linked to it picks up the change instantly — no need to touch user records or permission grants.

Connection Lifecycle

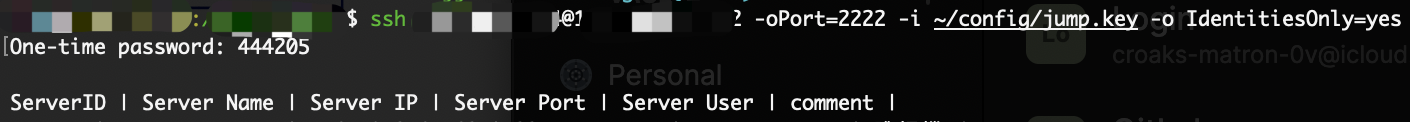

Here is what happens when an engineer types ssh alice@jump-host -p 2222:

1. TCP Accept & SSH Handshake

The sshserver.Server.Serve() loop accepts the TCP connection and hands it to handleConn() in a goroutine. The x/crypto/ssh library performs the SSH handshake using the server’s host key (auto-generated on first run and persisted to disk).

2. Public Key Authentication

The publicKeyCallback loads all non-deleted users from the database and compares the client’s offered public key against stored keys using SHA-256 fingerprint matching. If a match is found, the username from the SSH connection is verified against the key owner.

A rate limiter tracks failures per IP and per username. After 10 failed attempts, the source is blocked for 5 minutes. Successful authentication resets the counter.

3. OTP Challenge (Optional)

If the matched user has is_enabled_otp set, the session prompts for a 6-digit TOTP code before proceeding. The implementation follows RFC 6238 with SHA1-HMAC, 30-second windows, and one-window clock skew tolerance.

4. Server Selection

The user sees a numbered menu of servers they have permission to access (active, non-expired permissions only). Alternatively, the direct-connect syntax alice@3 embeds the server link ID in the SSH username, skipping the menu entirely.

5. Proxy to Remote

Once a server is selected, Jump:

- Opens a TCP connection to the remote server.

- Performs a second SSH handshake using the stored credentials (private key or password).

- Opens a session channel, requests a PTY, and starts a shell.

- Spawns two goroutines for bidirectional data copying.

- Forwards window-change requests from the client to the remote.

The client-to-remote path includes a line buffer that extracts and logs each command to the operation_log table — providing a full audit trail without any agent on the remote server.

6. Disconnection

When either side closes the connection, both channels are torn down, a “disconnect” event is logged, and the user returns to the server selection menu (or the SSH session ends).

The Admin UI

The admin UI is a server-rendered web application using Go’s html/template and Bootstrap. It provides full CRUD for every entity in the system: users, servers, auth methods, links, permissions, and a read-only log viewer with configurable limits (100 / 500 / 1000 / 2000 entries).

User creation through the admin UI automatically generates an RSA 2048-bit key pair and displays the private key for download. If OTP is enabled, a provisioning URI is generated for scanning into authenticator apps.

The admin UI currently runs without authentication, which is acceptable when bound to a private network or localhost. For production deployments exposed to the internet, it should sit behind a reverse proxy with its own auth layer.

CLI-First Provisioning

Beyond the serve command, the binary doubles as a CLI tool for headless provisioning:

# Create a user and save their private key

jump add-user -name alice -email [email protected] -otp -key-out alice.key

# Register a remote server

jump add-server -name prod-web-1 -ip 10.0.1.10 -port 22

# Store a credential

jump add-auth -type key -user deploy -key-file /path/to/deploy.key

# Link server + credential

jump link-server-auth -server-id 1 -auth-id 1

# Grant access (with optional expiration)

jump grant -user-id 1 -link-id 1 -expire "2026-12-31 23:59:59"

Every subcommand writes to the same SQLite file the server reads, so you can script onboarding and offboarding in CI/CD pipelines or Ansible playbooks.

Deployment

Jump ships as a single static binary. The Dockerfile uses a multi-stage build: golang:1.24-bookworm for compilation, debian:bookworm-slim for the runtime image. The final container exposes ports 2222 and 8080, with the database and host key persisted via a volume mount.

docker run -d \

-p 2222:2222 \

-p 8080:8080 \

-v jump-data:/data \

jump serve -db /data/jump.db

No environment variables to configure. No config files to template. The SQLite file is the configuration.

Design Trade-offs

No clustering. SQLite means a single writer. For teams that need HA, you would swap the storage layer to PostgreSQL and run multiple replicas — but most teams that need a bastion host don’t need HA on the bastion itself. If it’s down, engineers can’t SSH in, but that’s also true of any single-point VPN.

No agent on remote servers. Command logging works by intercepting keystrokes at the proxy layer. This means it captures what the user typed, not what the shell executed (aliases, shell expansions, etc.). For compliance, this is usually sufficient; for forensic-grade auditing, pair it with auditd on the remote hosts.

No web terminal. Jump is SSH-native. If you want browser-based access, tools like Apache Guacamole can sit in front of Jump’s SSH port.

Unprotected admin UI. This is intentional for simplicity. In production, bind it to 127.0.0.1 and front it with nginx + basic auth, or expose it only through a VPN.

What I’d Add Next

- Session recording — capture the full terminal stream (not just commands) as asciinema-compatible files for replay.

- RBAC groups — group-based permission grants instead of per-user assignments.

- Admin UI authentication — built-in auth for the web UI, possibly reusing the same SSH key infrastructure.

- Webhook notifications — alert on login, connection to sensitive servers, or permission expiration.

- Metrics endpoint — expose Prometheus metrics for active sessions, auth failures, and connection latency.

Wrapping Up

Jump is deliberately minimal. It solves one problem well: giving a team centralized, auditable SSH access to their servers without requiring anything beyond a single binary and an SQLite file.

The architecture bets on Go’s x/crypto/ssh for correctness and performance, SQLite for operational simplicity, and a normalized permission model for flexibility. It’s the kind of tool you deploy on a Friday afternoon and forget about until you need to answer “who accessed prod last Tuesday” — and then it earns its keep.

The source code is not public yet. But if you are interested in the project, you can contact me via email.